It’s not enough to consume excellent literature. If it’s a truly great book, it moves you to do something.

We’re not going to sit idly by after hearing about Tom Sawyer’s caving adventure, we’ve got to go find one for ourselves. We’re not just going to read about the challenge of starting a fire from scratch in Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet, we’ve got to try and build one ourselves.

How else could we possibly understand the magic of growing new things after reading The Secret Garden until we feel the dirt in our own hands, water, wait and wonder as we watch new life unfurl? How better to delight in foraging for edible foods when reading Elizabeth Enright’s Gone-Away Lake than going out and finding them for ourselves? How could we properly revel in the writings of John Muir, if we’ve never been to the mountains and marveled at their majesty?

Or appreciate the work of Theodore Roosevelt, doubling our National Parks, saving 230 million acres of public land from deforestation in a matter of 8 years, if we never go visit them?

As educators, we understand the importance of reading all the things, but we mustn’t stop there. If the goal in the end is action, change, and contribution, it’s not enough to just read about nature. Charlotte Mason wrote, “The question is not, — how much does the youth know? when he has finished his education — but how much does he care?” What’s the point of learning all of this stuff about trees and animals if they’re gone in 40 years? In his book, Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv writes, “If we want our kids to grow up and save the environment, they have to love it first.” This is the next crucial step in our great work as parents and educators.

Great literature may introduce us, but at some point we have to put the books down and go outside.

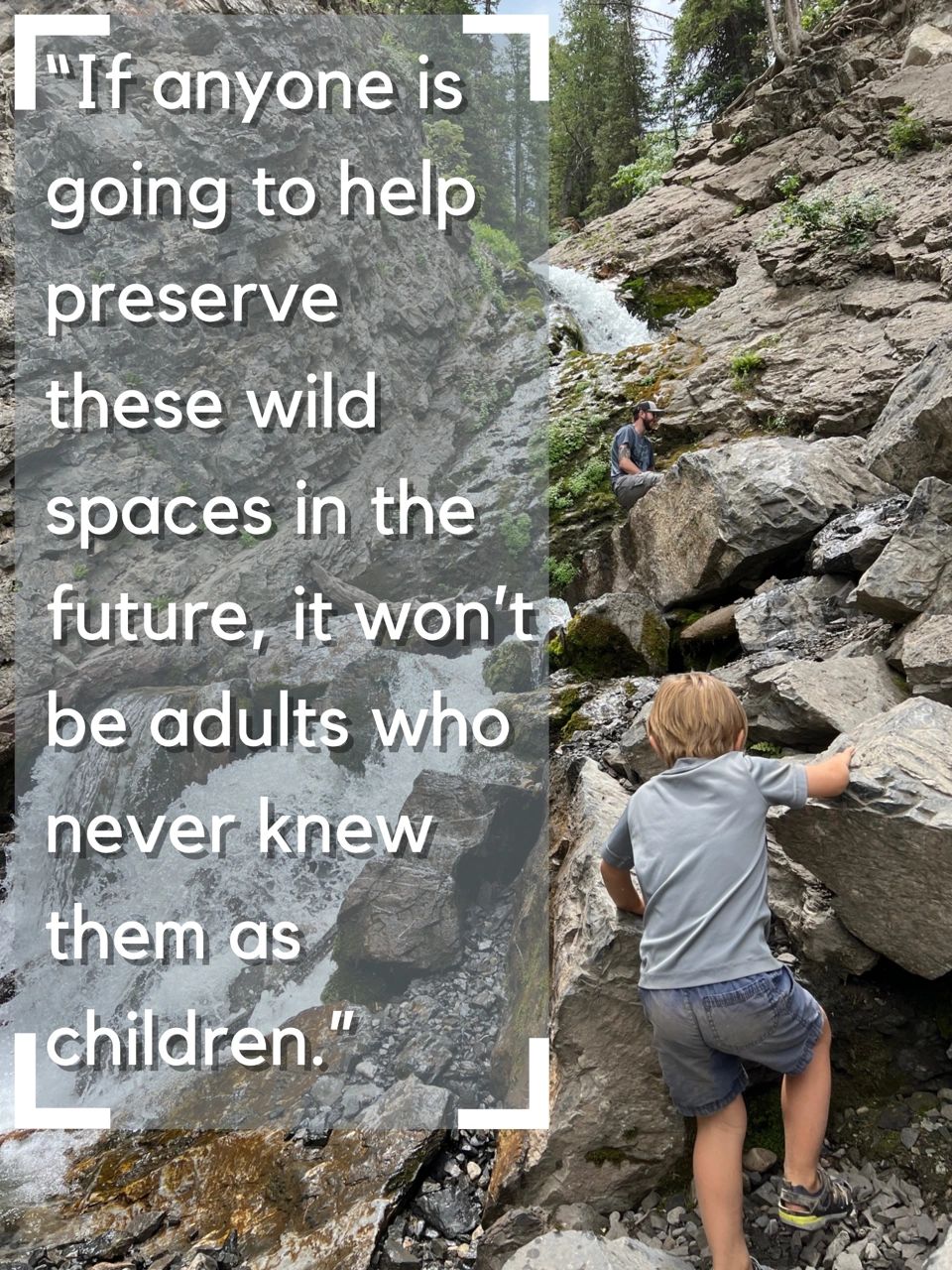

We may not be able to take regular road trips to Yosemite, but as we set aside regular time to be outside in our local parks, we’re planting seeds of earth-saving importance as we introduce and kindle our children’s relationship with the outdoors. When we make space in our schedules for them to free play and explore, we make space for a love of the wild to grow in their hearts. If anyone is going to help preserve these wild spaces in the future, it won’t be adults who never knew them as children.

Some days we spend outside feel like a “free day” away from the tablework of homeschooling, a “cheat day” even. But then I remind myself it IS schoolwork, even though it doesn’t feel like it. “School isn’t supposed to be a polite form of incarceration. It should be a portal to the wider world” Louv writes. Though the learning may be incalculable. How does one measure progress in a child’s fascination with spiny lizards? It’s impossible to grade the work done on the creative thinking it requires to assemble a natural bridge over a creek.

It’s not enough to simply READ My Side of the Mountain and be done with it, you have to see those hunting birds up close, meet a falconer, ask him 1,000 questions. You have to drink tea, eat homemade blueberry jam, crack wild nuts, and roast your food over an open fire. You have to ID plants and animal tracks and scat and climb the trees and make your own secret wild home to truly appreciate the book and let it burrow into these precious hearts. Read it, taste it, live it, know it. I can attest from hundreds of kids and parents in our book club that this integration from paper to life is the most fun type of learning.

That’s the power of a great book and an amazing community of like-minded parents who love doing life with their kids as co-adventuring lifelong learners. These are all things you could do together as a family with minimal effort when inspired by your recent reading. If you want to enjoy learning with others, join or establish your own book club (I recommend you start with Ainsley Arment’s Wild and Free Book Club: 28 Activities to Make Books Come Alive for inspiration).

Let’s remember that as we protect the time in our kids’ schedules for reading, writing and arithmetic in order to strive for excellence in education, there is an equally important time to put the books down and get outside for unstructured play in order for our children to fall in love with wild spaces. It’s a crucial part of the work, not to be missed for the sake of not only their overall education, but for our grandchildren’s future experiences in their own natural places (or lack thereof). It’s the courageous work of releasing the urgent for the necessary.

And how delightful it is, to be barefoot in the woods.

Arment, Ainsley. Wild and Free Book Club: 28 Activities to Make Books Come Alive. Harper One, 2021.

Louv, Richard. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder. Algonquin Books, 2004.

Mason, Charlotte. School Education: Developing a Cirriculum Original Homeschooling #3. London, England, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, 1925.

Rosenstock, Barb. The Camping Trip that Changed America: Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, and Our National Parks. Dial Books, 2012.

Photo credit: Gina McKnight

Jenny Fifield is a wife and homeschooling mom of 3 who spends her days co-adventuring and chasing wonder with her kids. She loves nature journaling, slow hikes, camping, writing & utilizing her Theatre degree reading aloud great books with all the voices. She co-leads a Barefoot University group and hosts a monthly book club for Homeschool families.